If we didn't have a Robert Boyle, we'd have needed to invent one. Boyle was the son of the wealthiest man in Great Britain, the Earl of Cork. Irish, he liked pubs, and chose his drinking buddies well: they called themselves the "Invisible College" and went on to help found the Royal Society, the first scientific society in the world with faculty from Gresham College.

Boyle was introduced to alchemy by George Starkey, a friend of a friend, and practiced alchemy almost his entire life. Boyle was an alchemist, but not wholly: he liked the experiments, but not the philosophy of alchemy.

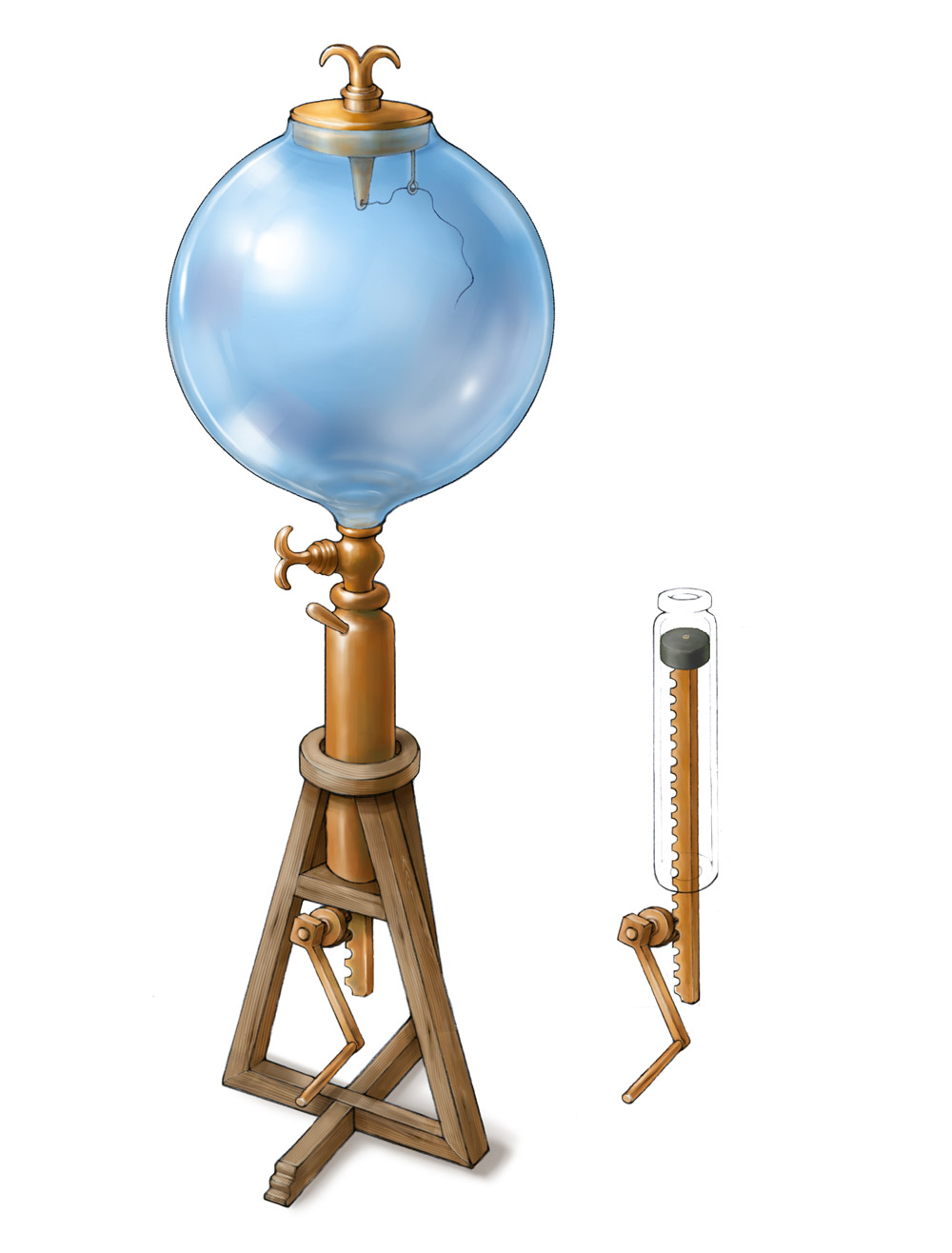

In 1659 Robert Hooke, of the Greatorex instrument makers, constructed for Boyle an air pump. It was a simple, awkward pump using rack and pinion gears to drive down a piston in a long, small cylinder. By repeatedly resetting the pump and taking another stroke, a chamber could be evacuated efficiently. Using the biggest glass hemisphere that could be made, Boyle put Torricelli's new barometer inside, and began to pump out the air. Observations of the pressure in the barometer showed that each stroke diminished the pressure about the same amount, until the limit of the pump was reached given the air leaks. What Boyle had done was the first scientific experiment.

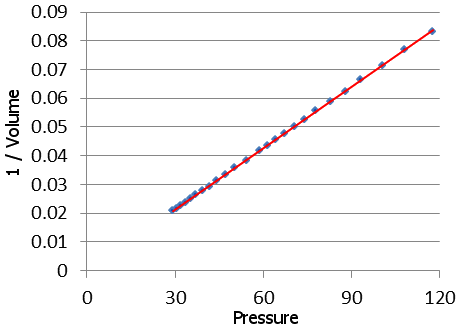

A graph of Boyle’s actual experimental results. Reciprocal Volume is plotted vs.

Pressure, producing a straight line. The data for the graph were taken from

Boyle’s work: A Defence of the Doctrine Touching the Spring And Weight of the Air.

His results were not welcomed in all quarters. Thomas Hobbes, one of the Empirical philosophers who believed that only by observation of nature could truths be obtained, had a huge problem with Boyles method. Boyle, Hobbs said, was not observing nature. He was observing not-nature, something man-made and manipulated and thus any conclusion was spurious.

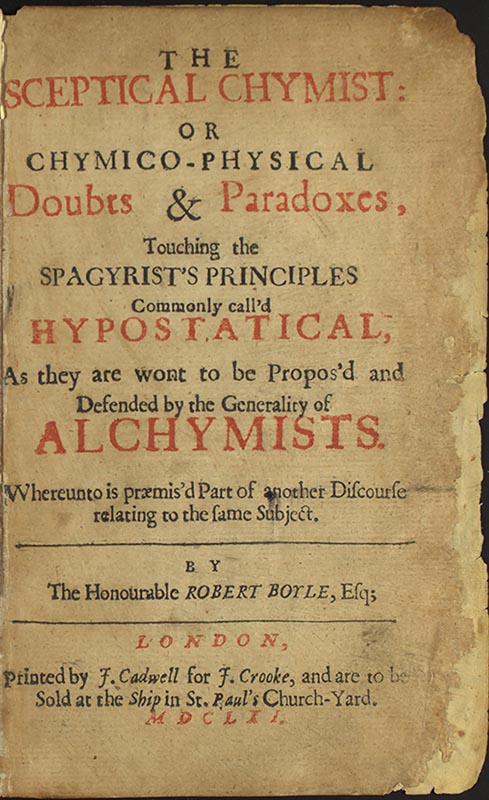

Boyle continued with other work on air, but turned aside to alchemy. He wrote a few papers, then wrote a book that some still think is an effort to trash alchemy; it wasn't. His book, The Skeptical Chymist (1661), was an attack on just a few parts of alchemy, particularly Paracelsian alchemy. His goal in studying alchemy was to take from alchemy the best of the experimental knowledge. Boyle had, since 1650, been thinking about experimentalism as a source of knowledge. He concluded that the only known information was experimentally-derived, and that is all one can trust. Gone are the philosophical mansions and "alchemical closets" of the past. His was pure experimentalism. He even went so far as to make sure the readers knew when he described an experiment that he had no intention of saying why the phenomenon occurred nor what it means.

From Experiment XXVII of New Experiments we have some philosophical musings:

Your Lordship will here perhaps expect, that as those who have treated of the Torricellian Experiment, have for the most part maintained the Affirmative, or the Negative of that famous Question, Whether or no that Noble Experiment infer a Vacuum? so I should on this occasion interpose my Opinion touching that Controversie, or at least declare whether or no, in our Engine, the exsuction of the Air do prove the place deserted by the Air suck'd out, to be truly empty, that is, devoid of all Corporeal Substance. But besides, that I have neither the leasure, nor the ability, to enter into a solemn Debate of so nice a Question; Your Lordship may, if you think it worth the trouble, in the Dialogues not long since referr'd to, find the Difficulties on both sides represented; which then made me yield but a very wavering assent to either of the parties contending about the Question: Nor dare I yet take upon me to determine so difficult a Controversie.

And somewhat more clearly in New Experiments:

And thought I pretend not to acquaint you, on this occasion, with any store of new Discoveries, yet possibly I shall be so happy, as to assist you to know somethings which you did formerly but suppose; and shall present you, if not with new Theories, at least with new Proofs of such as are not yet become unquestionable.

He's not doing this for the philosopher's sake, this is new, different. This is experimental endeavor for its own sake, to learn by observing.

[Oddly, Boyle again uses the word "theory" when he introduces, in 1662, what we now call Boyle's Law. You really need to read Wooton's The Invention of Science to make sense of the new usage of scientific words like 'law,' 'experiment,' 'hypothesis,' 'theory,' and 'discovery' that happen between 1650 and 1665.]

He also made a big point of how to argue and debate experimental information:

- Always argue the experimental facts, and that only, since that is all that matters. Never argue the person, because then you have at least three things you need to argue: the facts, the other person's ego, and all his supporters. Just stick to the facts and you job is three-times easier.

- When you do an experiment, always have in mind having witnesses. Witnesses can support you by simply being there and later telling honestly what they saw. Invite a few wise natural philosophers, or better yet, form a Society full of such people and perform the experiment there. Or better even than that, invite hundreds to attend and make a show of it. The more the merrier, because witnesses turn into your supporters.

- When you publish, try to describe your experiment in such detail that any reader can replicate your experiment. But since Boyle himself recognized that he would not be replicating his own fundamental work no one else was gong to either, so instead describe experiment so that the reader can picture himself there, observing the experiment himself, making himself a witness. Pictures are needed, and a very humble and non-egotistical writer, else the reader might think the writer is trying to convince without proof.

All these principles are now the core of chemistry writing. Boyle went so far as to demonstrate all these principles in his writing and in his experimentation, the most important of which are New Experiments and Continuation:

- 1660 – New Experiments Physico-Mechanical: Touching the Spring of the Air and their Effects

- 1661 – The Sceptical Chymist

- 1662 – Whereunto is Added a Defence of the Authors Explication of the Experiments, Against the Obiections of Franciscus Linus and Thomas Hobbes (a book-length addendum to the second edition of New Experiments Physico-Mechanical)

- 1663 – Considerations touching the Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy (followed by a second part in 1671)

- 1666 – Origin of Forms and Qualities according to the Corpuscular Philosophy. (A continuation of his work on the spring of air demonstrated that a reduction in ambient pressure could lead to bubble formation in living tissue. This description of a viper in a vacuum was the first recorded description of decompression sickness.)[39]

- 1669 – A Continuation of New Experiments Physico-mechanical, Touching the Spring and Weight of the Air, and Their Effects

- 1674 – Animadversions upon Mr. Hobbes's Problemata de Vacuo

- 1676 – Experiments and Notes about the Mechanical Origin or Production of Particular Qualities, including some notes on electricity and magnetism

- 1678 – Observations upon an artificial Substance that Shines without any Preceding Illustration

- 1681– Discourse of Things Above Reason

He sets forth four propositions:

- Proposition I.

- It seems not absurd to conceive that at the first production of mixt bodies, the universal matter whereof they among other parts of the universe consisted, was actually divided into little particles of several sizes and shapes variously moved.

- Proposition II.

- Neither is it impossible that of these minute particles divers of the smallest and neighboring ones were here and there associated into minute masses or clusters, and did by their coalitions constitute great store of such little primary concretions or masses as were not easily dissipable into such particles as composed them.

- Proposition III.

- I shall not peremptorily deny, that from most such mixt bodies as partake either of animals or vegetable nature, there may by the help of the fire be actually obtained a determinate number (whether three, four, or five, or fewer or more) of substances, worthy of differing denominations.

- Proposition IV.

- It may likewise be granted, that those distinct substances, which concretes generally either afford or are made up of, may without very much inconvenience be called the elements or principles of them.

He is interested in what makes a compound vs. an element. In the end he will propound Corpuscular Theory, a predecessor of atomic theory that will come 145 years later. The major themes in Skeptical Chymist are, to quote Wikipedia,

Boyle first argued that fire is not a universal and sufficient analyzer of dividing all bodies into their elements, contrary to Jean Beguin and Joseph Duchesne. To prove this he turned for support to Jan Baptist van Helmont whose Alkahest was reputed to be a universal analyzer.

Boyle rejected the Aristotelian theory of the four elements (earth, air, fire, and water) and also the three principles (salt, sulfur, and mercury) proposed by Paracelsus. After discussing the classical elements and chemical principles in the first five parts of the book, in the sixth part Boyle defines chemical element in a manner that approaches more closely to the modern concept:

- I now mean by Elements, as those Chymists that speak plainest do by their Principles, certain Primitive and Simple, or perfectly unmingled bodies; which not being made of any other bodies, or of one another, are the Ingredients of all those call'd perfectly mixt Bodies are immediately compounded, and into which they are ultimately resolved.[4]

However, Boyle denied that any known material substances correspond to such "perfectly unmingled bodies." In his view, all known materials were compounds, even such substances as gold, silver, lead, sulfur, and carbon.

I won't quote from Skeptical Chymist. It is, in my reading, the most difficult book to read in the English language. It's odd, too, since we have many exampled of Boyle making perfect sense. Overlong, overworked, obtuse to a fault, wasting more words in unneeded phraseology than it used profitably. Find a copy and try to read it yourself. You can't.

I'll quote one of his works, from [An Historical Account] of a Degradation of Gold Made by an Anti-Elixir: A Strange Chymical Narative (London 1678). By "Chymists" he means alchemists.

“The Publisher to the Reader”

Having been allowed the liberty of perusing the following paper at my own lodging, I found myself strongly tempted by the strangeness of the things mention’d in it, to venture to release it: the knowledge I had of the author’s inclination to gratifie the Virtuosi, forbidding me to despair of his pardon, if the same disposition prevail’d with me, to make the curious partakers with me of so surprising a piece of philosophical news. And, though it sufficiently appear’d that the insuing conference was but a continuation of a larger discourse; yet, considering that this part consists chiefly, not to say only, of a narrative, which (if I may so speak) stands upon its own legs, without any need of depending upon any thing that was deliver’d before; I thought it was no great venture, nor incongruity, to let it come abroad by itself. And, I the less scrupled to make this publication because I found that the Honorable Mr. Boyle confesses himself to be fully satisfied of the Truth, of as much of the matter of fact, as delivers the phoenomena of the tryal; the truth whereof was further confirm’d to me, by the testimony and particular account, which that most learned and experience’d physitian, who was assistant to Pyrophilus in making the experiment, and with whom I have the honor to be acquainted (being now in London) gave me with his own mouth, of all the circumstances of the tryal. And, where the truth of that shall be once granted, there is little cause to doubt that the novelty of the thing will sufficiently indear the relation: especially to those that are studious of the higher arcana of the Hermetick Philosophy. For most of the phoenomena here mentioned will probably seem wholly new, not only to vulgar Chymists, but also to the greatest part of the more knowing Spagyrists [the current word for Paracelsian alchemists] and Natural Philosophers themselves: none of the orthodox authors, as far as I can remember, having taken notice of such an Anti-Elixir. And, though Pyrophilus’s scrupulousness (which makes him very unwilling to speak the utmost of a thing) allowes it to be a deterioration into an imperfect mettal onely; yet, to tell the truth, I think it was more imbas’d than so; for the part left of it (and kept for some farther discoveries) which I once got a sight of, looks more like a mineral, or Marchasite, then like any imperfect mettal: and therefore this degradation is not the same, but much greater, than that which Lullius doth intimate in some places. These considerations make me presume it will easily be granted, that the effects of this Anti-Philosophers Stone, as I think it may not unfitly be call’d, will not only seem very strange to Hermetick, as well as other Philosophers, but may prove very instructive to speculative wits; especially if Pyrophilus shall please to acquaint them with that more odd Phoenomenon, which he mentions darkly in the close of his discourse.

An Historical Account of the Degradation of Gold by an Anti-Elixir

After the whole Company had, as it were by common consent, continued silent for some time, which others spent in reflections upon the preceding conference, and Pyrophylus, in the consideration of what he was about to deliver; this Virtuoso at length stood up, and addressing himself to the rest, “I hope, Gentlemen,” sayes he, “that what has been already discoursed, has inclin’d, if not perswaded you to think, that the exaltation or change of other metals into Gold is not a thing absolutely impossible; and, though I confess, I cannot remove all your doubts, and objections, or my own, by being able to affirm to you, that I have with my own hands made projection (as Chymists are wont to call the sudden transmutation made by a small quantity of their admirable Elixir) yet I can confirm much of what hath been argued for the possibility of such a sudden change of a metalline body, by a way, which, I presume, will surprize you. For, to make it more credible, that other metals are capable of being graduated, or exalted into gold by way of projection; I will relate to you that by the like way, Gold has been degraded, or imbased.”

The novelty of this Preamble having much surprised the auditory, at length, Simplicius, with a disdainful smile, told Pyrophilus, “that the Company would have much thanked him, if he could have assured them, that he had seen another mettal exalted into Gold; but that to find a way of spoiling Gold, was not onely an useless discovery, but a prejudicial practice.”

Pyrophilus was going to make some return to this animadversion, when he was prevented by Aristander, who, turning himself to Simplicius, told him, with a countenance and tone that argued some displeasure, “If Pyrophilus had been discoursing to a company of goldsmiths or of merchants, your severe reflection upon what he said would have been proper: but, you might well have forborn it, if you had considered, as I suppose he did, that he was speaking to an assembly of Philosophers and Virtuosi, who are wont to estimate experiments, not as they inrich mens purses, but their brains, and think knowledge especially of uncommon things very desirable, even when ‘tis not accompanyed with any other thing, than the light that still attends it and indears it. It hath been thought an useful secret, by a kind of retrogradation to turn Tin and Lead into brittle bodies, like the ores of those metals. And if I thought it proper, I could shew, that such a change might be of use in the investigation of the nature of those metals, besides the practical use that I know may be made of it. To find the nature of wine, we are assisted, not only by the methods of obtaining from it a spirit; but by the ways of readily turning it into vinegar; the knowledge of which ways hath not been despised by Chymists or Physitians, and hath at Paris, and divers other places, set up a profitable trade. ‘Tis well known that divers eminent Spagyrists have reckon’d amongst their highest Arcana the ways by which they pretended (and I fear did but pretend) to extract the Mercury of Gold, and consequently destroy that metal; and ‘twere not hard to shew by particular instances, that all the experiments wherein bodies are in some respects deteriorated, are not without distinction to be rejected or despis’d; since in some of them, the light they may afford may more than countervail the degradation of a small quantity of matter, though it be Gold itself. And indeed,” continues he, “if we will consider things as philosophers, and look upon them as nature hath made them, not as opinion hath disguised them; the prerogatives and usefulness of Gold, in comparison of other metals, is nothing near so great as alchymists and usurers imagine. For, as it is true, that Gold is more ponderous, and more fix’d, and perhaps more difficult to be spoiled, than Iron; yet these qualities (whereof the first makes it burthensom, and the two others serve chiefly but to distinguish the true from counterfeit) are so balanced by the hardness, stiffness, springiness, and other useful qualities of Iron; that if those two metals I speak of, (Gold and Iron) were equally plentiful in the world, it is scarce to be doubted, but that men would prefer the more useful before the more splendid, considering how much worse it were for mankind to want hatchets and knives and swords, than coin and plate? Wherefore,” concludes he, “I think Pyrophilus ought to be both desired and incouraged to go on with his intended discourse, since whether Gold be or not be the best of metals, an assurance that it may be degraded, may prove a novelty very instructive and perhaps more so than the transmutation of a baser metal into a nobler . . .”

Pyrophilus perceiving by several signs that he needed not add anything of apologetical to what Aristander had already said for him, resumed his discourse by saying, “I was going, Gentlemen, when Simplicius diverted me, to tell you that looking upon the vulgar objections that have been wont to be fram’d against the possibility of metalline transmutations, from the authority and prejudices of Aristotle and the School Philosophers, as arguments that in such an assembly as this need not now be solemnly discuss’d; I consider that the difficulties that really deserve to be call’d so, and are of weight even with Mechanical Philosophers, and judicious Naturalists, are principally these. First, that the great change that must be wrought by the Elixir (if there be such an agent) is effected upon bodies of so stable and almost immutable a nature as metals. Next, that this great change is said to be brought to pass in a very short time. And thirdly (which is yet more strange), that this great and suddain alteration is said to be effected by a very small, and perhaps inconsiderable proportion of the transmuting powder. To which three grand difficulties, I shall add another that to me appears, and perhaps will seem to divers of the new Philosophers, worthy to be lookt upon as a fourth, namely, the notable change that must by a real transmutation be made in the Specifick Gravity of the matter wrought upon: which difficulty I therefore think not unworthy to be added to the rest, because upon several trials of my own and other men, I have found no known quality of Gold (as its colour, malleableness, fixity, or the like) so difficult, if not so impossible, to be introduc’d into any other metalline matter, as the great Specifick Gravity that is peculiar to Gold. So that, Gentlemen,” concludes Pyrophilus, “if it can be made appear that Art has produc’d an Anti-Elixir, (if I may so call it) or agent that is able in a very short time, to work a very notable, though deteriorating, change upon a metal; in proportion to which, its quantity is very inconsiderable; I see not why it should be thought impossible that Art may also make a true Elixir, or powder capable of speedily transmuting a greater proportion of a baser metal into Silver or Gold; especially if it be considered, that those that treat of these Arcana, confess that ‘tis not every matter which may be justly called the Philosophers Stone, that is able to transmute other metals in vast quantities; since several of these writers (and even Lully himself) make differing orders or degrees of the Elixir, and acknowledge that a Medicine or tincture of the first or lowest order will not transmute above ten times its weight of an inferior metal.”

Pyrophilus having at this part of his discourse made a short pawse to take breath, Crattippus took occasion from his silence to say to him, “I presume, Pyrophilus, I shall be disavowed by very few of these Gentlemen, if I tell you that the Company is impatient to hear the narrative of your experiment, and that if it do so much as probably make out the particulars you have been mentioning, you will in likelyhood perswade most of them, and will certainly oblige them all. I shall therefore on their behalf as well as my own, sollicite you to hasten to the historical part of a discourse that is so like to gratifie our curiosity.”

The Company having by their unanimous silence testified their approbation of what Crattippus had said; and appearing more than ordinarily attentive,

“As I was one day abroad,” saith Pyrophilus, “to return visits to my friends, I was by a happy providence (for it was beside my first intention) directed to make one to an ingenious foreigner, with whom a few that I had received from him, had given me some little acquaintance.

Whilst this gentleman and I were discoursing together of several matters, there came in to visit him a stranger, whom I had but once seen before; and though that were in a promiscuous company, yet he addressed himself to me in a way that quickly satisfied me of the greatness of his civility; which he soon after also did of that of his curiosity. For the Virtuoso, in whose lodgings we met, having (to gratifie me) put him upon the discourse of his voyages, the curious stranger entertained us an hour or two with pertinent and judicious answers to the questions I askt him about places so remote, or so much within land, that I had not met with any of our English navigators or travellers that had penetrated so far as to visit them . . . I made the more haste to propose such questions to him, as I most desired to be satisfied about; and among other things, enquiring whether in the Eastern parts [of the world] he had travers’d, he had met with any Chymists; he answered me that he had; and that though they were fewer, and more reserved than ours, yet he did not find them all less skilful. And on this occasion, before he left the town to go aboard the ship he was to overtake; he in a very obliging way put into my hands at parting a little piece of paper, folded up, which he said contained all that he had left of a rarity he had received from an Eastern Virtuoso, and which he intimated would give me occasion both to remember him, and to exercise my thoughts in uncommon speculations.

The great delight I took in conversing with a person that had travelled so far, and could give me so good an account of what he had seen, made me so much resent the being so soon deprived of it, that though I judg’d such a Vertuoso would not, as a great token of his kindness, have presented me a trifle, yet the present did but very imperfectly consoal me for the loss of so pleasing and instructive a conversation.

Nevertheless, that I might comply with the curiosity he himself had excited in me, and know how much I was his debtor, I resolved to see what it was he had given me, and try whether I could make it do what I thought he intimated, by the help of those few hints rather than directions how to use it, which the parting haste he was in (or perhaps some other reason best known to himself) confin’d him to give me. But in regard that I could not but think the experiment would one way or other prove extraordinary, I thought fit to take a witness or two and an assistant in the trying of it; and for that purpose made choice of an experienced Doctor of Physick, very well vers’d in the separating and copelling8 of metals.”

“Though the Company,” says Heliodorus, “be so confident of your sincerity and wariness, that they would give credit even to unlikely experiments upon your single testimony; yet we cannot but approve your discretion in taking an assistant and a witness, because in nice and uncommon experiments we can scarce use too much circumspection, especially when we have not the means of reiterating the tryal: for in such new, as well as difficult cases, ’tis easie even for a clear-sighted experimenter to overlook some important circumstance, that a far less skilful bystander may take notice of.”

“As I have ever judged,” saith Pyrophilus, “that cautiousness is a very requisite qualification for him that would satisfactorily make curious experiments; so I thought fit to imploy a more than ordinary measure of it in making a tryal, whose event I imagined might prove odd enough. And therefore having several times observed that some men are prepossessed, by having a particular expectation rais’d in them, and are inclined to think that they do see that happen which they think they should see happen, I resolved to obviate this prejudication as much as innocently I could, and (without telling him any thing but the truth, to which philosophy as well as religion obliges us to be strictly loyal) I told him but thus much of the truth, that I expected that a small proportion of a powder presented me by a foreign Virtuoso would give a brittleness to the most flexible and malleable of metals, Gold itself. Which change I perceiv’d he judged so considerable and unlikely to be effected, that he was greedy of seeing it severely try’d.

Having thus prepared him not to look for all that I my self expected, I cautiously opened the paper I lately mentioned, but was both surprized and troubled (as he also was), to find in it so very little powder, that in stead of two differing tryals that I designed to make with it, there seem’d very small hope left that it would serve for one (and that but an imperfect one neither). For there was so very little powder that we could scarce see the colour of it (save that as far as I could judge it was of a darkish red) and we thought it not only dangerous but useless to attempt to weigh it, in regard we might easily lose it by putting it into, and out of the balance; and the weights we had were not small enough for so despicable a quantity of matter, which in words I estimated at an eighth part of a grain: but my assistant (whose conjecture I confess my thoughts inclin’d to prefer) would allow it to be at most but a tenth part of a grain. Wherefore seeing the utmost we could reasonably hope to do with so very little powder was to make one tryal with it, we weighed out in differing balances two drams of Gold that had been formerly English coyn, and that I caused by one that I usually imploy to be cupell’d with a sufficient quantity of Lead, and quarted, as they speak, with refin’d Silver, and purg’d Aqua fortis, to be sure of the goodness of the Gold: these two drams I put into a new crucible, first carefully annealed, and having brought them to fusion by the meer action of the fire, without the help of Borax, or any other Additament (which course, though somewhat more laborious than the most usual we took to obviate scruples) I put into the well-melted metal with my own hand the little parcel of powder lately mentioned, and continuing the vessel in the fire for about a quarter of an hour, that the powder might have time to defuse itself every way into the metal, we poured out the well-melted Gold into another crucible that I had brought with me, and that had been gradually heated before to prevent cracking. But though from the first fusion of the metal, to the pouring out, it had turn’d in the crucible like ordinary Gold, save that once my assistant told me he saw that for two or three moments it lookt almost like an Opale; yet I was somewhat surpriz’d to find when the matter was grown cold, that though it appear’d upon the balance that we had not lost anything of the weight we put in, yet in stead of fine Gold, we had a lump of metal of a dirty colour, and as it were overcast with a thin coat, almost like half vitrified Litharge; and somewhat to increase the wonder, we perceived that there stuck to one side of the crucible a little globule of metal that lookt not at all yellowish, but like coarse Silver, and the bottom of the crucible was overlaid with a vitrified substance whereof one part was of a transparent yellow, and the other of a deep brown, inclining to red; and in this vitrified substance I could plainly perceive sticking at least five or six little globules that lookt more like impure Silver than pure Gold. In short, this stuff look[ed] so little like refin’d, or so much as ordinary, Gold, that though my Friend did much more than I marvel at this change, yet I confess I was surpriz’d at it myself. For though in some particulars it answered what I lookt for, yet in others, it was very differing from that which the donor of the powder had, as I thought, give[n] me ground to expect. Whether the cause of my disappointment were that (as I formerly intimated) this Virtuoso’s haste or design made him leave me in the dark; or whether it were that finding my self in want of sufficient directions, I happily pitcht upon such a proportion of materials, and way of operating, as were proper to make a new discovery, which the excellent giver of the powder had not design’d or perhaps thought of . . .

[Pyrophilus next descibes the testing of the newly transmuted metal.] And first, having rubb’d it upon a good touchstone, whereon we had likewise rubb’d a piece of Coyn’d silver, and a piece of Coyn’d Gold, we manifestly found that the mark left upon the stone by our mass between the marks of the two other metals, was notoriously more like the touch of the Silver than to that of the Gold. Next, having knockt our little lump with a hammer, it was (according to my prediction) found brittle, and flew into several pieces. Thirdly, (which is more) even the insides of those pieces lookt of a base dirty colour, like that of Brass or worse, for the fragments had a far greater resemblance to Bell-metal,12 than either to Gold or to Silver. To which we added this fourth, and more considerable, examen; that having carefully weigh’d out one dram of our stuff (reserving the rest for trials to be suggested by second thoughts) and put it upon an excellent new and well-neal’d cupel, with about half a dozen times its weight of Lead, we found, somewhat to our wonder, that though it turn’d very well like good Gold, yet it continued in the fire above an hour and an half, (which was twice as long as we expected) and yet almost to the very last the fumes copiously ascended, which sufficiently argu’d the operation to have been well carried on . . .”

“There yet remain’d,” saith Heliodorus, “one examen more of your odd metal, which would have satisfied me, at least as much as any of the rest, of its having been notably imbas’d: for if it were altered in its specifick gravity, that quality I have always observ’d (as I lately perceiv’d you also have done) to stick so close to Gold, that it could not by an additament so inconsiderable in point of bulk, be considerably altered without a notable and almost essential change in the texture of the metal.”

To this pertinent discourse, Pyrophilus, with the respect due to a person that so worthily sustain’d the dignity he had of presiding in that choice Company, made this return: “I owe you, Sir, my humble thanks for calling upon me to give you an account I might have forgotten, and which is yet of so important a thing, that none of the other Phænomena of our experiment seem’d to me to deserve so much notice. Wherefore I shall now inform you, that having provided my self of all the requisites to make hydrostatical tryals (to which perhaps I am not altogether a stranger) I carefully weighed in the water the ill-lookt mass (before it was divided for the coupelling of the above-mentioned dram) and found, to the great confirmation of my former wonder and conjectures, that in stead of weighing about nineteen times as much as a bulk of water equal to it, its proportion to that liquor was but that of fifteen, and about two thirds to one: so that its specifick gravity was less by about 3 1/3 than if it had been pure Gold it would have been.”

At the recital of this notable circumstance, superadded to the rest, the generality of the Company, and the President too, by looking and smiling upon one another, express’d themselves to be as well delighted as surpriz’d; and after the murmuring occasion’d by the various whispers that pass’d amongst them, was a little over, Heliodorus address’d himself to Pyrophilus, and told him, “I need not, and therefore shall not, stay for an express order from the Company to give you their hearty thanks: for as the obliging stranger did very much gratifie you by the present of his wonderful powder, so you have not a little gratified us by so candid and particular a narrative of the effects of it; and I hope,” continues he, “that if you have not yet otherwise dispos’d of that part of your deteriorated Gold that you did not cupel, you will sometime or other favour us with a sight of it . . .”

[Crattippus then comments on the larger implications of Pyrophilus’s report.] “And though I freely grant that some old copper metals are of good use in history, to keep alive by their inscriptions the memory of the taking of a town, or the winning of a battel; though these be but things that almost every day are somewhere or other done, yet I think Pyrophilus’s imbas’d metal is much to be preferr’d, as not only preserving the memory, but being an effect of such a victory of Art over Nature, and the conquering of such generally believ’d insuperable difficulties, as no story that I know of gives us an example of . . .” [Heliodorus then calls upon Pyrophilus to present “what Corrollaries he thinks fit to propose from what he hath already delivered.”] Pyrophilus responds, “our experiment plainly shews that Gold, though confessedly the most homogeneous, and the least mutable of metals, may be in a very short time (perhaps not amounting to many minutes) exceedingly chang’d, both as to malleableness, colour, homogeneity, and (which is more) specific gravity; and all this by so very inconsiderable a proportion of injected powder, that since the Gold that was wrought on weighed two of our English drams, and consequently an hundred and twenty grains, an easie computation will assure us that the Medicine did thus powerfully act, according to my estimate, (which was the modestest) upon near a thousand times, (for ‘twas above nine hundred and fifty times) its weight of Gold, and according to my assistants estimate, did (as they speak) go on upon twelve hundred; so that if it were fit to apply to this Anti-Elixir (as I formerly ventur’d to call it) what is said of the true Elixir by divers of the Chymical Philosophers, who will have the virtue of their Stone increas’d in such a proportion, as that at first ‘twill transmute but ten times its weight; after the next rotation an hundred times, and after the next to that a thousand times, our powder may in their language be stil ‘d a Medicine of the third order.”

[Aristander provides a final defense of pursuing the arcana of chemistry.] “The Computation,” saith Aristander, “is very obvious, but the change of so great a proportion of metal is so wonderful and unexampled, that I hope we shall among other things learn from it this lesson, That we ought not to be so forward as many men otherwise of great parts are wont to be, in prescribing narrow limits to the power of Nature and Art, and in condemning and deriding all those that pretend to, or believe, uncommon things in Chymistry, as either Cheats or Credulous. And therefore I hope, that though (at least in my opinion) it be very allowable to call Fables, Fables, and to detect and expose the impostures or deceits of ignorant or vain-glorious pretenders to chymical mysteries, yet we shall not be too hasty and general censur[er]s of the sober and diligent indigators of the Arcana of chymistry, [to] blemish (as much as in us lies) that excellent Art itself, and thereby disoblige the genuine Sons of it, and divert those that are indeed possessors of noble secrets, from vouchsafing to gratifie our curiosity, as we see that one of them did Pyrophilus’s, with the sight at least, of some of their highly instructive rarities.”

From New Experiments, where Boyle is describing experiments using a partial vacuum:

EXPERIMENT XXXIII.

BUt in regard we have not yet been able to empty so great a Vessel as our Receiver, so well as we can the Cylinder it self; our Pump alone may afford us a nobler instance of the force of the Air we live in, insomuch, that by help of this part of our Engine, we may give a pretty near ghess at the strength of the Atmosphere, computed as a weight. And the way may be this; First, the Sucker being brought to move easily up and down the Cylinder, is to be impelled to the top of it: Then the Receiver must be taken off from the Pump, that the upper Orifice of the Cylinder remaining open, the Air may freely succeed the Sucker, and therefore readily yield to its motion downwards. This done, there must be fasten'd to one of the Iron Teeth of the Sucker, such a weight as may just suffice to draw it to the bottom of the Cylinder. And having thus examin'd what weight is necessary to draw down the Sucker, when the Atmosphere makes no other than the ordinary resistance of the Air against its descent; the Sucker must be again forc'd to the top of the Cylinder, whose upper Orifice must now be exactly closed; and then (the first weight remaining) we easily may, by hanging a Scale to the above-mention'd Iron (that makes part of the Sucker) cast in known weights so long, till in spight of the reluctancy of the Atmosphere the Sucker be drawn down. For to these weights in the Scale, that of the Scale it self being added, the sum will give us the weight of a Column of Air, equal in Diameter to the Sucker, or to the cavity of the Cylinder, and in length to the height of the Atmosphere.

According to this method we did, since the writing of the last Experiment, attempt to measure the pressure of the Atmosphere, but found it more difficult than we expected, to persorm it with any accurateness; for though by the help of the Manubrium the Sucker moved up and down with so much ease, that one would have thought that both its convex surface, and the concave one of the Cylinder were exquisitely smooth, and as it were slippery; yet when the Sucker came to be moved onely with a dead weight or pressure (that was not (like the force of him that pumped) intended as occasion required) we found that the little rufnesses or other inequalities, and perhaps too, the unequal pressure of the Leather against the cavity of the Cylinder, were able, now and then, to put a stop to the descent or ascent of the Sucker, though a very little external help would easily surmount that impediment; and then the Sucker would, for a while, continue its formerly interrupted motion, though that assistance were withdrawn. But this discouragement did not deter us from prosecuting our Experiment, and endeavouring, by a carefull trial, to make it as instructive as we could. We found then that a Leaden Weight, of 28 pounds (each consisting of sixteen Ounces) being fastned to one of the teeth of the Sucker, drew it down closely enough, when the upper Orifice of the Cylinder was left open: though by the help of Oyl and Water, and by the frequent moving the Sucker up and down with the Manubrium, its motion in the Cylinder had been before purposely facilitated. This done, the upper Orifice of the Cylinder was very carefully and closely stopped, the Valve being likewise shut with its wonted Stopple well oyl'd, after the Sucker had been again impell'd up to the top of the Cylinder. Then to the precedent twenty eight pound, we added a hundred and twelve pounds more; which forcing down the Sucker, though but leisurely, we took off the twenty eight pound weight; and being unable to procure just such weights as we would have had, we hung on, instead of it, one of fourteen pound: but found that, with the rest, unable to carry down the Sucker. And to satisfie our selves, and the Spectators, that it was the resistance of the ambient Air that hinder'd the descent of so great a weight, after that we had try'd that upon unstopping the Valve, and thereby opening an access to the external Air, the Sucker would be immediately drawn down. After this, I say, we made this farther Experiment, That having by a Man's strength forcibly depress'd the Sucker to the bottom of the Cylinder, and then fastned weights, to the above-named Iron that makes part of that Sucker, the pressure of the external Air finding little or nothing in the cavity of the evacuated Cylinder to resist it, did presently begin to impell the Sucker, with the weights that clogg'd it, towards the upper part of the Cylinder; till some such accidental Impediment, as we formerly mention'd, check'd its course. And when that rub, (which easily might be,) was taken out of the way, it would continue its ascent to the top, to the no small wonder of those By-standers, that could not comprehend how such a weight could ascend, as it were, of it self; that is, without any invisible force, or so much as Suction to list it up. And indeed it is very considerable, that though possibly there might remain some particles of Air in the Cylinder, after the drawing down of the Sucker; yet the pressure of a Cylinder of the Atmosphere, somewhat less than three Inches in Diameter (for, as it was said in the description of our Engine, the cavity of the Cylinder was no broader) was able, uncompress'd, not only to sustain, but even to drive up a weight of an hundred and odd pounds: for besides the weight of the whole Sucker it self, which amounts to some pounds, the weights annexed to it made up an hundred and three pounds, besides an Iron Bar, that by conjecture weighed two pounds more; and yet all these together fall somewhat short of the weight which we lately mention'd, the resistance of the Air, to have held suspended in the cavity of the Cylinder.

And though (as hath been already acknowledg'd (we cannot peradventure, obtain by the recited means so exact an account as were to be wish'd, of what we would discover: Yet, if it serve us to ground conjectures more approaching to the Truth, than we have hitherto met with, I hope it will be consider'd (which a famous Poet judiciously says)

Est quoddam prodire tenus, si non datur ultra.

Peradventure it will not be impertinent to annex to the other circumstances that have been already set down concerning this Experiment, That it was made in Winter, in Weather neither Frosty nor Rainy, about the change of the Moon, and at a place whose latitude is near about 51 degrees and a half: For perhaps the force or pressure of the Air may vary, according to the Seasons of the Year, the temperature of the Weather, the elevation of the Pole, or the phases of the Moon; all, or even any of them seeming capable to alter either the height or consistence of the incumbent Atmosphere: And therefore it would not be amiss if this Experiment were carefully tried at several times and places, with variety of circumstances. It might also be tried with Cylinders of several Diameters, exquisitely fitted with Suckers, that we might know what proportion several Pillars of the Atmosphere bear to the weights they are able to sustain or lift up; and consequently, whether the increase or decrement of the resistance of the ambient Air, can be reduced to any regular proportion to the Diameters of the Suckers: These, and divers other such things which may be try'd with this Cylinder, might most of them be more exactly try'd by the Torricellian Experiments, if we could get Tubes so accurately blown and drawn, that the cavity were perfectly Cylindrical.

To dwell upon all the several Reflexions, that a speculative Wit might make upon this and the foregoing Experiment, (I mean the thirty third and thirty second) would require almost a Volume; whereas our occasions will scarce allow us time to touch upon three or four of the chief Inferences that seem deducible from them, and therefore we shall content our selves to point at those few.

And first, as many other Phaenomena of our Engine, so especially, the two lately mention'd Experiments, seem very much to call in question the received Opinion of the nature or cause of Suction. For it's true indeed, that when men suck, they commonly use some manifest endeavour by a peculiar motion of their Mouths, Chests, and some other conspiring parts, to convey to them the body to be suck'd in. And hence perhaps they have taken occasion, to think that in all Suction there must be some endeavour or motion in the sucking to attract the sucked Body. But in our last Experiment it appears not at all how the upper part of the empty'd Cylinder that remains moveless all the while, or any part of it, doth at all endeavour to draw to it the depressed Sucker and the annexed weights. And yet those that behold the ascension of the Sucker, without seriously considering the cause of it, do readily conclude it to be raised by something that powerfully Sucks or attracts it, though they see not what that may be or where it lurks. So that it seems not absolutely necessary to Suction, that there be in the Body, which is said to suck, an endeavour or motion in order thereunto, but rather that Suction may be at least for the most part reduced to Pulsion, and its effects ascrib'd to such a pressure of the neighbouring Air upon those Bodies (whether Aërial, or of other natures) that are contiguous to the Body that is said to attract them, as is stronger, than that substance, which possesseth the cavity of that sucking Body, is able to resist. To object here, that it was some particles of Air remaining in the emptied Cylinder that attracted this weight to obviate a Vacuum, will scarce be satisfactory; unless it can be clearly made out by what little hooks, or other grappling Instruments, the internal Air could take hold of the Sucker; how so little of it obtained the force to lift up so great a weight; and why also, upon the letting in of a little more Air into one of our evacuated Vessels, the attraction is, instead of being strengthened, much weakned; though, if there were danger of a Vacuum before, it would remain, notwithstanding this ingress of a little Air. For that still there remained in the capacity of the exhausted Cylinder store of little rooms, or spaces empty or devoid of Air, may appear by the great violence wherewith the Air rusheth in, if any way be open'd to it. And that 'tis not so much the decrement of the Vacuum within the cavity of the vessel that debilitates the attraction, as the Spring of the included Air (whose presence makes the decrement) that doth it by resisting the pressure of the external Air, seems probable, partly from the Disability of vacuities, whether greater or lesser, to resist the pressure of the Air; and partly by some of the Phaenomena of our Experiments, and particularly by this Circumstance of the Three and Thirtieth, that the Sucker was, by the pressure of the Ambient Air, impell'd upwards with its weight hanging at it, not onely when it was in the bottom of the Cylinder, and consequently left a great Vacuum in the cavity of it; but when the Sucker had been already impell'd almost to the top of the Cylinder, and consequently, when the Vacuum that remain'd was become very little in comparison of that which preceded the beginning of the Sucker's ascension.

In the next place, these Experiments may teach us, what to judge of the vulgar Axiom received for so many Ages as an undoubted Truth in the Peripatetick Schools; That Nature abhors and flyeth a Vacuum, and that to such a degree, that no humane power (to go no higher) is able to make one in the Universe; wherein Heaven and Earth would change places, and all its other Bodies rather act contrary to their own Nature, than suffer it. For, if by a Vacuum we will understand a place perfectly devoid of all corporeal Substance, it may indeed then, as we formerly noted, be plausibly enough maintained that there is no such thing in the world; but that the generality of the Plenists, (especially till of late years some of them grew more wary) did not take a Vacuum in so strict a sense, may appear by the Experiments formerly, and ev'n to this day imploy'd by the Deniers of a Vacuum, to prove it impossible that there can be any made. For when they alledge (for Instance) that when a man sucks Water through a long Pipe, that heavy Liquor, contrary to its Nature, ascends into the Sucker's mouth, only, to fill up that room made by the Dilatation of his Breast and Lungs, which otherwise will in part be empty. And when they tell us, that the reason why if a long Pipe exactly clos'd at one end be filled top-full of Water, and then inverted, no Liquor will fall out of the open Orifice; Or, to use a more samiliar Example, when they teach, that the cause, why in a Gardiner's watering Pot shaped conically, or like a Sugar-Loaf, fill'd with Water, no Liquor falls down through the numerous holes at the bottom, whilst the Gardiner keeps his Thumb upon the Orifice of the little hole at the top, and no longer; must be that if in the case proposed the Water should descend, the Air being unable to succeed it, there would be le•t at the upper and deserted part of the Vessel a Vacuum, that would be avoided if the hole at the top were open'd. When (I say) they alledge such Experiments, the tendency of them seems plainly to import, that they mean, by a Vacuum, any space here below that is not filled with a visible body, or at least with Air though it be not quite devoy'd of all Body whatsoever. For why should Nature, out of her detestation of a Vacuum, make Bodies act contrary to their own tendency, that a place may be fill'd with Air, if its being so were not necessary to the avoiding of a Vacuum.

Taking then a Vacuum in this vulgar and obvious sense, the common opinion about it seems lyable to several Exceptions, whereof some of the chief are suggested to us by our Engine.

It will not easily then be intelligibly made out, how hatred or aversation, which is a passion of the Soul, can either for a Vacuum, or any other object, be supposed to be in Water, or such like inanimate Body, which cannot be presumed to know when a Vacuum would ensue; if they did not bestir themselves to prevent it: nor to be so generous as to act contrary to what is most conducive to their own particular preservation for the publique good of the Universe. As much then of intelligible and probable Truth, as is contain'd in this Metaphorical Expression, seems to amount but to this; That by the Wise Authour of Nature (who is justly said to have made all things in number, weight and measure,) the Universe, and the parts of it, are so contriv'd, that it is as hard to make a Vacuum in it, as if they studiously conspir'd to prevent it. And how far this it self may be granted, deserves to be farther consider'd.

For in the next place, our Experiments seem to teach, that the supposed Aversation of Nature to a Vacuum is but accidental, or in consequence, partly of the Weight and Fluidity, or, at least, Fluxility of the Bodies here below; and partly, and perhaps principally, of the spring of the Air, whose restless endeavour to expand it self every way, makes it either rush in it self, or compel the interposed Bodies into all spaces, where it finds no greater resistance than it can surmount. And that in those motions which are made ob fugam Vacui (as the common phrase is) Bodies act without such generosity and consideration, as is wont to be ascrib'd to them, is apparent enough in our 32d Experiment, where the torrent of Air, that seem'd to strive to get into the empty'd Receiver, did plainly prevent its own design by so impelling the Valve, as to make it shut the only Orifice the Air was to get out at. And if afterwards either Nature, or the internal Air, had a design the external Air should be attracted, they seem'd to prosecute very unwisely by continuing to suck the Valve so strongly; when they found that by that Suction the Valve it self could not be drawn in: Whereas by forbearing to suck, the Valve would by its own weight have fallen down, and suffer'd the excluded Air to return freely, and to fill again the exhausted Vessel.

And this minds me to take notice of another deficiency, pointed at by our Experiments in the common Doctrine of those Plenists we reason with; for many of those unusual motions in Bodies, that are said to be made to escape a Vacuum, seem rather made to fill it. For why, to instance in our newly mention'd Experiment, as soon as the Valve was depressed by the weight we hung at it, should the Air so impetuously and copiously rush into the cavity of the Receiver; if there were before no vacant room there to receive it? and if there were, then all the while the Valve kept out the Air, those little spaces in the Receiver, which the corpuscles of that Air afterwards fill'd, may be concluded to have remain'd empty. So that the seeming violence, imploy'd by Nature on the occasion of the evacuating of the Vessel, seems to have come too late to hinder the making of Vacuities in the Receiver, and only to have, as soon as we permitted, fill'd up with Air those that were already made.

And as for the care of the publique good of the Universe ascrib'd to dead and stupid Bodies, we shall only demand, why in our 19th Experiment, upon the Exsuction of the ambient Air, the Water deserted the upper half of the Glass-Tube; and did not ascend to fill it up, till the external Air was let in upon it: whereas by its easie and sudden regaining that upper part of the Tube, it appeared both that there was there much space devoid of Air, and that the Water might with small or no resistance have ascended into it, if it could have done so without the impulsion of the re-admitted Air; which, it seems, was necessary to mind the Water of its formerly neglected Duty to the Universe.

Nay, for ought appeareth, even when the excluded Air, as soon as 'twas permitted, rush'd violently into our exhausted Receiver, that flowing in of the Air proceeded rather from the determinate Force of the Spring of the neighbouring Air, than from any endeavour to fill up, much less to prevent vacuity's. For though when as much Air as will, is gotten into our Receiver our present Opponents take it for granted that it is full of Air; yet if it be remembred that when we made our 17th Experiment we crouded in more Air to our Receiver than it usually holds; and if we also consider (which is much more) that the Air of the same consistence with that in our Receiver may in Wind-guns, as is known, and as we have tryed, be compressed at least into half its wonted room (I say at least, because some affirm, that the Air may be thrust into an 8th, or a yet smaller part of its ordinary extent) it seems necessary to admit either a notion of condensation and rarefaction that is not intelligible, or that in the capacity of our Receiver when presumed to be full of Air, there yet remain'd as much of space as was taken up by all the Aërial corpuscles, unpossessed by the Air. Which seems plainly, to infer that the Air that rush'd into our empty'd vessel did not doe it precisely to fill up the Vacuities of it, since it left so many unfill'd, but rather was thrust in by the pressure of the contiguous Air: which as it could not, but be always ready to expand it self, where it found least resistance, so was it unable to fill the Receiver any more, than untill the Air within was reduc'd to the same measure of Compactness with that without.

We may also from our two already often mention'd Experiments farther deduce, that, (since Natures hatred of a Vacuum is but Metaphorical and Accidental, being but a consequence or result of the pressure of the Air and of the Gravity, and partly also of the Fluxility of some other Bodies) The power she makes use of to hinder a Vacuum, is not (as we have else-where also noted) any such boundless thing as men have been pleased to imagine. And the reasons why in the former Experiments, mentioned in favour of the Plenists, Bodies seem to forget their own Natures to shun a Vacuum, seems to be but this; That in the alledged cases the weight of that Water that was either kept from falling or impell'd up, was not great enough to surmount the pressure of the contiguous Air; which, if it had been, the Water would have subsided, though no Air could have succeeded. For not to repeat that Experiment of Monsieur Paschal (formerly mention'd to have been tryed in a Glass exceeding 32. Foot) wherein the inverted Pipe being long enough to contain a competent-weight of Water, that Liquor freely ran out at the lower Orifice: Not to mention this (I say) we saw in our nineteenth Experiment, that when the pressure of the ambient Air was sufficiently weakn'd, the Water would fall out apace at the Orifice even of a short Pipe, though the Air could not succeed into the room deserted by it. And it were not amiss if tryal were made on the tops of very high Mountains, to discover with what case a Vacuum could be made near the confines of the Atmosphere, where the Air is probably but light in comparison of what it is here below. But our present (three and thirtieth) Experiment seems to manifest, not onely that the power, exercis'd by Nature, to shun or replenish a Vacuum, is limitted, but that it may be determin'd even to Pounds and Ounces: Insomuch that we might say, such a weight Nature will sustain or will lift up to resist a Vacuum in our Engine; but if an Ounce more be added to that weight, it will surmount Her so much magnifi'd detestation of Vacuities. And thus, My Lord, our Experiments may not onely answer those of the Plenists, but enable us to retort their Arguments against themselves: since, if that be true which they alleadge, that, when Water falls not down according to its nature, in a Body wherein no Air can succeed to fill up the place it must leave, the suspension of the Liquor is made Ne detur Vacuum, (as they speak) it will follow, that if the Water can be brought to subside in such a case, that deserted space may be deem'd empty, according to their own Doctrine; especially, since Nature (as they would perswade us) bestirs her self so mightily to keep it from being deserted.

I hope I shall not need to remind Your Lordship, that I have all this while been speaking of a Vacuum, not in the strict and Philosophical sense, but in that more obvious and familiar one that hath been formerly declar'd.

And therefore I shall now proceed to observe in the last place, that our 33d Experiment affords us a notable proof of the unheeded strength of that pressure which is sustain'd by the Corpuscles of what we call the free Air, and presume to be uncompressed. For, as fluid and yielding a Body as it is, our Experiment teacheth us, That ev'n in our Climate, and without any other compression than what is (at least here below) Natural, or (to speak more properly) ordinary to it, it bears so strongly upon the Bodies whereunto it is contiguous, that a Cylinder of this free Air, not exceeding three Inches in Diameter is able to raise and carry up a weight, amounting to between sixteen and seventeen hundred Ounces. I said even in our Climate, because that is temperate enough; * and as far as my observations assist me to conjecture, the Air in many other more Northern Countries may be much thicker, and able to support a greater weight: which is not to be doubted of, if there be no mistake in what is Recorded concerning the Hollanders, that were forc'd by the Ice to Winter in Nova Zembla, namely, That they found there so condens'd an Air, that they could not make their Clock goe, ev'n by a very great addition to the weights that were wont to move it.

I suppose Your Lordship will readily take notice, that I might very easily have discoursed much more fully and accurately than I have done, against the common opinion touching Suction, and touching natures hatred of a Vacuum. But I was willing to keep my self to those considerations touching these matters, that might be verified by our engine it self, especially, since, as I said at first, it would take up too much time to insist particularly upon all the Reflexions that may be made even upon our two last Experiments. And therefore passing to the next, I shall leave it to Your Lordship to consider how far these tryals of ours will either confirm or disfavour the new Doctrine of several eminent Naturalists, who teach, That in all motion there is necessarily a Circle of Bodies, as they speak, moving together; and whether the Circles in such motion be an Accidental or Consequential thing or no.

John Freind, the Newtonian chemist, lectured

No Body has brought more Light into this Art than Mr. Boyle, that famous Restorer of Experimental Philosophy: Who nevertheless has not so much laid a new Foundation of Chymistry, as he has thrown down the old; he has left us plentiful Matter, from whence we may draw out a true Explication of things, but the Explication it self he has but very sparingly touch'd upon.

Chymical Lectures, London, 1712, p. 4.