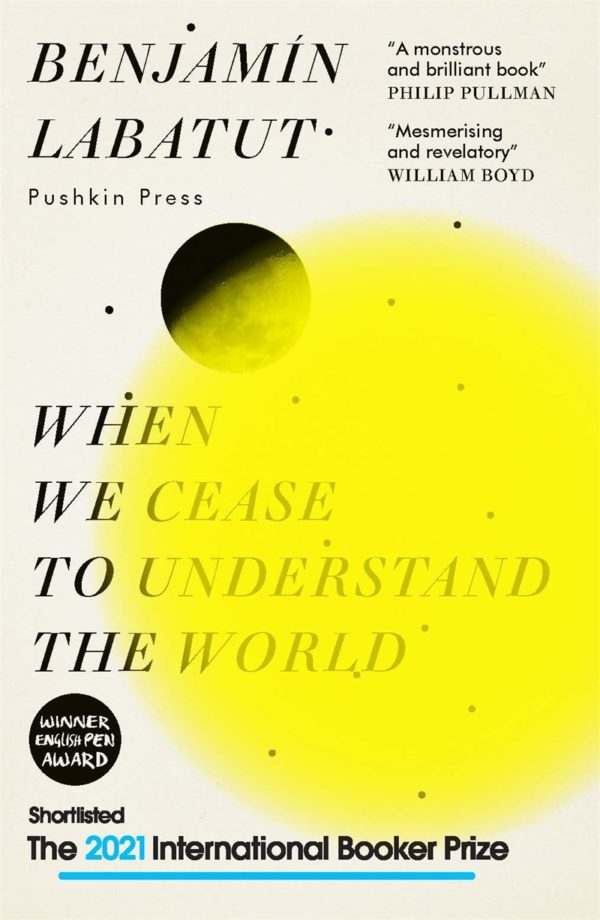

When We Cease to Understand the World, by Benjamín Labatut (2020) is an odd book. It's short, full of the stories of 20th-centure scientists, which is the problem: they are stories.

Labatut's stories are part fiction, part fact, which alone makes it very interesting to me, because I believe most of science, as scientists describe it, is also part fiction, part fact. I see his book as a lay version of what scientists to to themselves: make the science fit into the context of a good story. This is the new mythology of science, and it's what bears science up above the boredom of the experiments and the measurements.

The stories are told in a sort of running narration of the influence of one scientist upon another, a version of James Burke's Connections series so popular on PBS in 1978 (you can watch them at the Internet Archive; I love watching them still). Except that Labatut's narrative takes us to madness, the madness experienced by the obsessions of these scientists to understand and to control. I think he meant the book as a description of the moral costs of doing science, of the personal cost to the scientists.

But only a few scientists from the past really knew how to do science, Robert Boyle and Antoine Lavoisier being the first two. Boyle was adamant that his efforts to do science had nothing to do with any sort of theory or explanation, in other words, the story; his efforts were all about the experiment. Hard-headed practicality was his method.

But we can't live without the story. We need to place what we know into the context of our lives, so story, theory, and mythology all blend to make observations real to us. Labatut demonstrates the role of story in science very nicely. It doesn't matter that it's fiction. It's the story we need.

When Ruth Franklin reviewed the book for The New Yorker, she said,

There is liberation in the vision of fiction’s capabilities that emerges here—the sheer cunning with which Labatut embellishes and augments reality, as well as the profound pathos he finds in the stories of these men. But there is also something questionable, even nightmarish, about it. If fiction and fact are indistinguishable in any meaningful way, how are we to find language for those things we know to be true?

"A Cautionary Tale About Science Raises Uncomfortable Questions About Fiction". The New Yorker. September 3, 2021.

She is totally on the right track; story and science have been blended together thousands of years before the first "scientist."

The alchemists lived on a sort of mythology that came from Plato and Aristotle. This mythology grew, changed, had different expressions, but the core set of beliefs remained unchanged as the stories passed from Hellenistic culture, to Muslim, to European Christian cultures. It's the mythology that ties all of alchemy together over 2000 years.

And what differentiates Boyle and Levoisier from the rest? Lack of idealism. To be a good scientist requires a disdain for the mythology, so that one can see the world as it is, not as it should be. Idealism is itself a mythology: "I can understand the world perfectly," says the idealist, "so I can choose for others their beliefs and course of action." It's a very evil thing to say, really, but only an idealist can say it.

And when the idealist put their ideas into action, they might notice the damage they do, and to calm their troubled brow will begin telling themselves stories.

P.S. Having said what I see as the big accomplishment of this book, I think it should never have been written. The author is an unreliable narrator of history, and it won't take long for the fiction in this book to show up in college classrooms as fact. I guess what bothers me most is the quotes from these people, with no reference to where they said it or where it was reported. It make me suspect all I read, even the things I previously thought were true.