One basic of a scientific theory is its ability to make predictions which can be tested. If those predictions are accurate, the theory holds. If they are not, the theory is wrong. This is Basic Science 101. Respectable scientists, seeing a prediction go bad, fix it pretty quick with a follow-up publication, though they won't often go back in the literature and retract the bad theory (those retractions only happen when someone else finds fraud in the data and makes it public; scientists are pretty self-aggrandizing that way: hide the bad, brag up the good).

Now I’m going to discuss how we would look for a new law. In general, we look for a new law by the following process. First, we guess it [audience laughter], no, don’t laugh, that’s the truth. Then we compute the consequences of the guess, to see what, if this is right, if this law we guess is right, to see what it would imply and then we compare those computation results to nature or we say compare to experiment or experience, compare it directly with observations to see if it works.

If it disagrees with experiment, it’s WRONG. In that simple statement is the key to science.

It doesn’t make any difference how beautiful your guess is, it doesn’t matter how smart you are, who made the guess, or what his name is… If it disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong. That’s all there is to it.

Richard Feynmann, 1964

Some scientists get away with bad theories by choosing fields of research where there is no future to predict: paleontologists, for example, won't have dinosaurs to study in the future, leaving them free to say anything they want. In my mind, they can't be scientists, for they can make no testable prediction. They are, in the mythology of science, stamp collectors.1

Those who deal with chaotic systems are in the same difficulty, only they do have the power to test their predictions. Their problem is that they can't predict the outcome, because of the chaos. Chaos is the name we give a system determined not by large factors, but by miniscule variations at an almost atomic scale. Unless that variability is well-described (requiring calculations involving 1012 to 1024 variables), the chaotic system can't be understood well enough to make a prediction, much less a reliable one. The climate is a chaotic system.

Last year the climate scientists predicted a worse-than-average hurricane season. But this has been one of the quietest hurricane seasons ever known. They missed the prediction by miles.

But what is the great sin of the climate "scientists?" Probably hubris. They know they have a chaotic system, and still they make predictions of its behavior. They know their predictions are crap, and still they go on TV and talk about them as though it were fact, thinking, perhaps, that convincing the morons out there that they do understand a chaotic system makes them right. It does take a moron to listen to their predictions over the years and conclude they are even at 50% accuracy. They aren't. Climate predictions are far below 50%.

Here's what a prediction looks like, a real prediction: the temperature in [preferred location here] in one year will be [this temperature] plus-or-minus one degree F. Or, the rain in the month of March in 2024 in [location] will be [this much] plus or minus x mm. But not even the weather forecasters can get this right one week out, not without rather major windows of possibilities, and a public with a very short memory.

It's getting to the point in some disciplines where the scientists and commentators use the weather-level of prediction to be the standard of how a theory is to make predictions. Gone is the exact prediction, which is the only standard that can work.

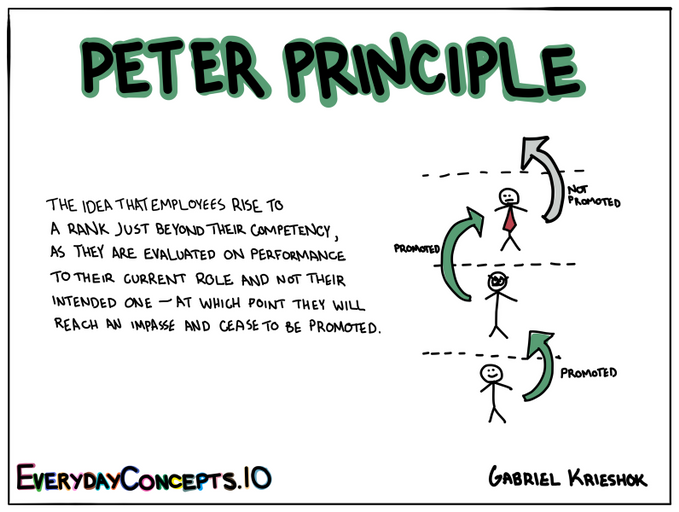

And how did we get to this sad state of affairs? Propaganda. Politics, Narcissism. It has many names, but the actual mechanism is more prosaic, I think: Incompetence. It's called the Peter Principle.

Employees rise to the rank where they just become incompetent, and that's where they stagnate and make all their mistakes. Common in government positions, industry, business, academia. Interestingly, education is not one of these. You can't get a Ph.D. if you are incompetent. It is at least very difficult.

And finding oneself incompetent to do the job for which you are paid a bundle, it would be difficult to admit that you have no idea what the future will bring, revealing your incompetence to your superiors. So the incompetent make public proclamations about the future, seemingly unaware that the public just heard what they said and will remember it. And when asked later about the failure of the prediction, will deny, push aside, attack the questioner, all those completely unscientific ways to respond to a specific challenge.

The scientific response to a challenge is to produce data which confirms your prediction, or to change your prediction. There is a core of humility needed to be a scientist. This was identified by Robert Boyle back in 1660. I'd quote him here but he is notoriously difficult to quote, being supremely long-winded in explaining everything in every sentence he writes. So I'll quote people who read and understand what Boyle said:

Boyle several times insisted that he was an innocent of the great theoretical systems of the seventeenth century. In order to reinforce the primacy of experimental findings, “I had purposely refrained from acquainting myself thoroughly with the intire system of either the Atomical, or the Cartesian, or any other whether new or received philosophy.” And, again, he claimed that he had avoided a systematic acquaintance with the systems of Gassendi, Descartes, and even of Bacon, “that I might not be prepossessed with any theory or principles.”2

Boyle’s “naked way of writing,” his professions and displays of humility, and his exhibition of theoretical innocence all complemented each other in the establishment and the protection of matters of fact. They served to portray the author as a disinterested observer and his accounts as unclouded and undistorted mirrors of nature. Such an author gave the signs of a man whose testimony was reliable. Hence, his texts could be credited and the number of witnesses to his experimental narratives could be multiplied indefinitely.

Shapin, Steven; Schaffer, Simon. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: 32 (Princeton Classics) (pp. 68-69). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

In fact, Shapin and Schaffer portray the scientific method as a social organization scientists use to find acceptable means of communicating the ideas they have.

We intend to display scientific method as crystallizing forms of social organization and as a means of regulating social interaction within the scientific community.

Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life (1985) by Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer, Princeton University Press, p. 14

Scientific method is more than a set of rules for trusting data or testing theories; they eventually settle on a phrase, the scientific way of life, to refer to the totality of complexities the scientist needs to address. But incompetence is never one of them. Incompetence is rejected out of hand. Boyle is right when he tried so hard to make everything about observable fact, matters of fact (that phrase originated in the Royal Society of London, which Boyle helped found in 1660, and which bears yet his insistence of provable observations as establishing fact3). Boyle hated the idea that you could approach an experiment with a specific outcome in mind; to be honest with yourself you learn to expect anything, for only then can you learn how nature behaves. Once you learn that, get proof of your observation by having witnesses, and if possible, write up your observations with such honesty that even a skeptic will have no cause to doubt your veracity.

Well, none of that happens in science today. Most things I read, from the abstract to the end, make me doubt that such a thing happened as was reported. Certainly not predictions.

Even this morning there was a news article proclaiming the discovery on Mars of organic molecules, a sign of past life on the planet. But that will almost certainly be quietly walked back when they recover the rock sample and test it properly. They used a technique called Raman spectroscopy, and that technique gives the identity of the molecule, but these reports lack that specific evidence. But the samples aren't scheduled to return until 2033, so until then the idea of past life on Mars will spread and likely become fully accepted. And when the samples come home, if they do (there is a history of returned samples being damaged before analysis, even from earth orbit, i.e. Stardust mission, 2006), the molecules won't be there and the announcement will go unheeded by the press because it doesn't conform to accepted beliefs.

Incompetence. Incompetence of the scientists involved to announce before they have proof, the narcissism of getting their name in the press, the self-aggrandizement (short lived though it may be) that drives the incompetent scientist to say they are right, even for a short time, with the hope (maybe not even that) that critical scientists won't notice what they've done.

But we see you. We recognize you for what you are.

Incompetent.

Do us a favor: demote yourself one step and get back to where you were competent. Then we can be proud of you.

And one other thing: NEVER take a prediction from anyone who can't describe NOW accurately.

1There is a mythology in science, mostly in its pith quotation history, like when Ernest Rutherford said that all science is physics, the rest is stamp collecting. There isn't any proof, and barely a hint, that he said it. See https://quoteinvestigator.com/2015/05/08/stamp/

2Boyle, “Some Specimens of an Attempt to Make Chymical Experiments Useful,” p. 355; idem, “Proëmial Essay,” p. 302; on the corrupting effects of “preconceived hypothesis or conjecture,” see idem, “New Experiments,” p. 47, and, for doubts about the correctness of Boyle’s professed unfamiliarity with Descartes and other systematists, see Westfall, “Unpublished Boyle Papers,” p. 63; Laudan, “The Clock Metaphor and Probabilism,” p. 82n; M. B. Hall, “The Establishment of the Mechanical Philosophy,” pp. 460-461; idem, Boyle and Seventeenth-Century Chemistry, chap. 3; idem, “Boyle as a Theoretical Scientist”; idem, “Science in the Early Royal Society,” pp. 72-73; Kargon, Atomism in England, chap. 9; Frank, Harvey and the Oxford Physiologists, pp. 93-97. Our concern here is not with the veracity of Boyle’s professions but with the reasons he made them and the purposes they were designed to serve.

3The motto of the Society, Nullius in verba, means "Take nobody's word for it." This is the major influence of Boyle on modern science, an influence almost no one, even modern chemists, knows happened.